The expert panel first convened in the spring of 2009 to establish the vision and purpose of the panel, discuss the process and schedule for producing the guidelines, and determine the critical areas to be addressed. Prior to this meeting, the expert panel participated in a conference call to introduce the panel’s work and discuss the overarching questions that should be answered by the guidelines. Before beginning the writing of the guidelines report, the expert panel divided its work into sections dealing with preventive care or health maintenance, recognition and management of acute SCD-related complications, recognition and management of chronicSCD-related complications, and the two most broadly assessed and available disease-modifying therapies for

SCD, hydroxyurea and chronic blood transfusions.

With the assistance of the methodology team and the supporting evidence center, the panel then developed key questions and literature search terms to identify evidence. The field of SCD has a limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or large prospective cohort studies to guide clinical decision making; therefore, few of the recommendations in this document are based on this highest quality evidence. For common health issues, the panel included the evidence-based recommendations of the USPSTF as well as vetted recommendations of other groups. These recommendations include the SCD reproductive-related recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), the immunization recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), and the acute and chronic pain management recommendations of the American Pain Society (APS). These recommendations are denoted as “Consensus—Adapted.

Recognizing the need to provide practical guidance for common problems that may lie outside of the panel’s evidence reviews or available science, in many areas the published evidence was supplemented by the expertise of the panel members, who have many years of experience in managing and studying individuals with SCD. Recommendations based on the opinions of the expert panel members are labeled as “Consensus—Panel Expertise.” Each is clearly labeled with the strength of the recommendation and the quality of evidence available to support it.

Evidence Review and Synthesis

Beginning in April 2010, the expert panel collaborated with an independent evidence synthesis group (hereafter referred to as the methodology team) that included methodologists, librarians, and research staff with expertise in conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses and appraising and summarizing evidence for the purpose of guideline development. The methodology team used the overarching questions, the key questions, and a list of specific guideline topics to draft an initial list of PICOS’-formatted critical questions for literature searches and formal evidence appraisal and vetting (see enappdixi3). The methodology team developed search strategies and then conducted literature searches and prepared the evidence tables and a summary of the body of the evidence (see http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidclincs/sed/indcx.htm).

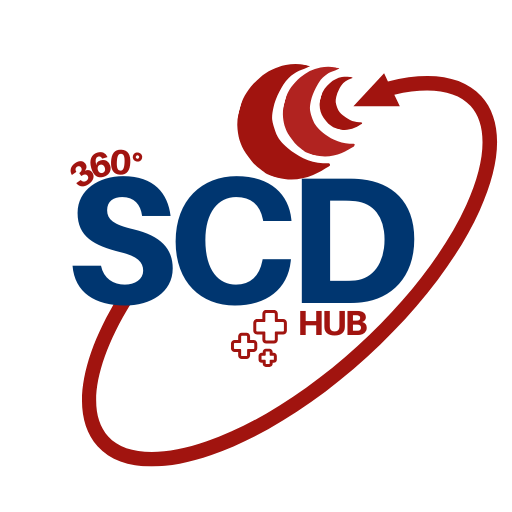

Exhibit 2 outlines the overall process for the evidence search, evidence synthesis, and recommendation development.

Literature Search

Due to the comprehensive scope of the guidelines, the search strategies for the systematic reviews were designed to have high sensitivity and low specificity; hence, the strategies were often derived from population and condition terms (e.g., people with SCD who have priapism) and not restricted or combined with outcome or intervention terms. To be inclusive of the available literature in the field, searches included randomized trials, nonrandomized intervention studies, and observational studies. Case reports and small case series were included only when outcomes involved harm (e.g., the adverse effects of hydroxyurea) or when rare complications were expected to be reported.

Literature searches involved multiple databases (e.g., Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, MEDLINE , Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), TOXLINE, and Scopus) and used controlled vocabulary (pre-specified) terms supplemented with keywords to define concept areas.

Evidence Synthesis

The initial literature searches performed to support these guidelines yielded 12,532 references. The expert panel also identified an additional 1,231 potentially relevant references. An updated search of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) added eight trials. All abstracts were reviewed independently by two reviewers using an online reference management system (DistillerSR—http://systematic-rcvicw.nct) until reviewers reached adequate agreement (kappa k0.90). A total of 1,575 original studies were included in the evidence tables. Methodologists developed evidence tables to summarize individual study findings and present the quality of evidence (i.e., confidence in the estimates of effect). The tables included descriptions of study population, SCD genotypes, interventions, and outcomes. Additional methodological details are discussed in each evidence table, including the search question, search strategy, study selection process, and list of excluded studies (see http://www.nhlbi.nih.Nov/Ruidclincs/scd/indcx.htm).

Evidence Framework

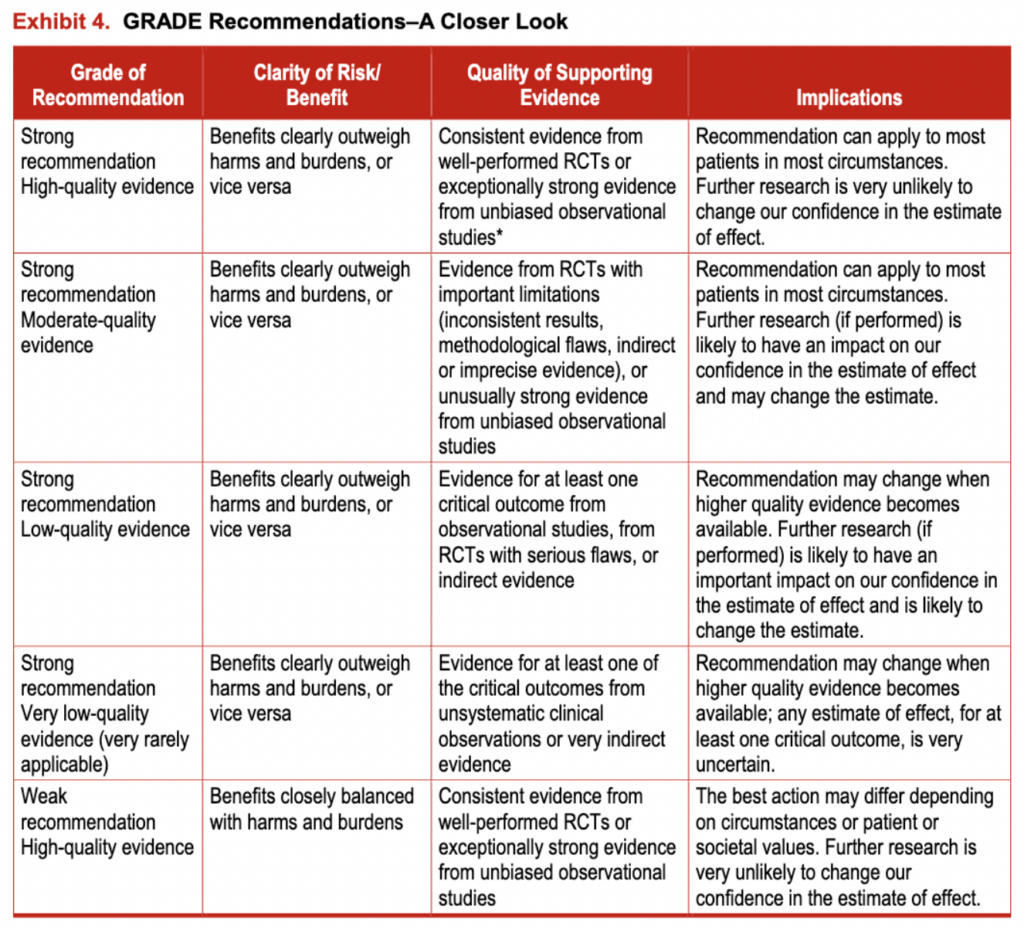

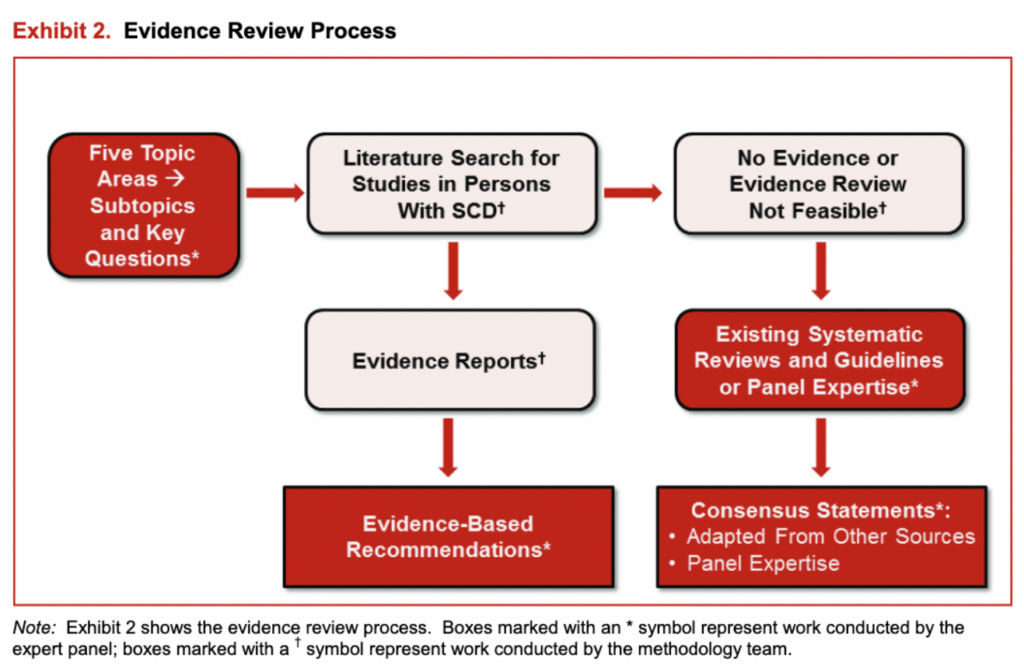

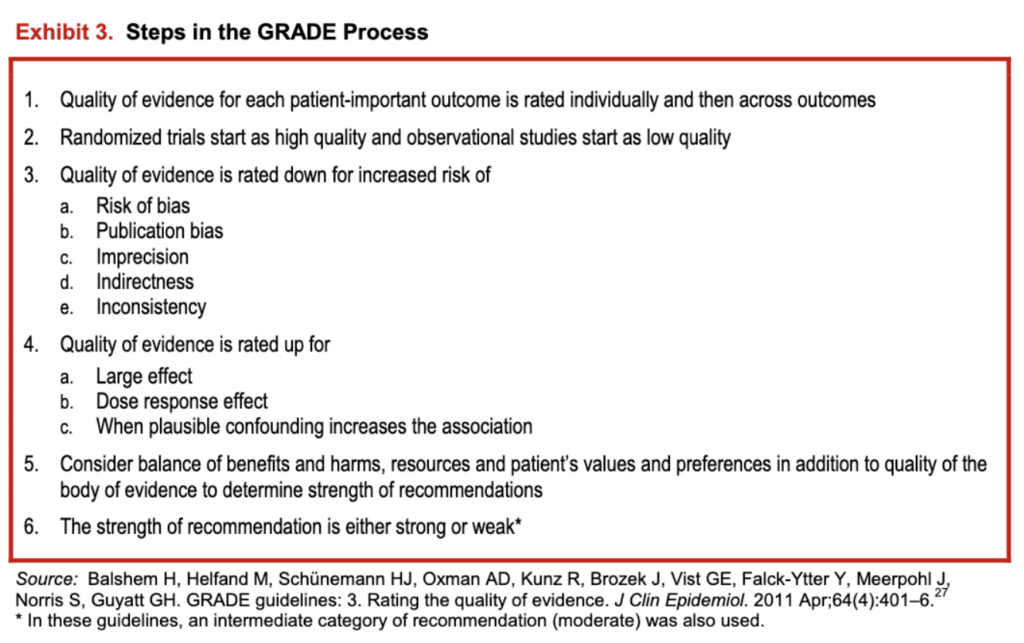

The methodology team used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework 25 to grade the quality of evidence, and, in concert with the panel, determine the strength of recommendations. The GRADE framework is accepted by more than 75 national and international. organizations (see exhibit 3). It provides the advantages of: (a) separately judging the quality of supporting evidence and strength of recommendations, and (b) incorporating factors other than evidence in decision making (e.g., the balance of benefits and harms; the perceived values and preferences of those with SCD; resources; and clinical and social context). GRADE emphasizes the use of patient-important outcomes (i.e., outcomes that affect the way patients feel, function, or survive) 26 over laboratory and physiologic outcomes

In the GRADE framework, the quality of evidence (in this case, the body of evidence) is rated as high, moderate, low, or very low.” The quality of evidence derived from randomized trials starts as “high,” and the quality of evidence derived from observational studies starts as “low.” The quality of evidence can then be lowered due to methodological limitations in individual studies (risk of bias), inconsistency across studies (heterogeneity), indirectness (the extent to which the evidence fails to apply to the specific clinical question in terms of the patients, interventions, or outcomes), imprecision (typically due to a small number of events or wide confidence intervals), and the presence of publication and reporting biases. Conversely, the quality of evidence can be upgraded in certain situations such as when the treatment effect is large or a dose-response relationship is evident.

Determining the Strength of Recommendations

The GRADE framework rates the strength of recommendations as “strong” or “weak.” However, the panel modified the GRADE system and used a third category—moderate—when they determined that patients would be better off if they followed a recommendation, despite there being some level of uncertainty about the magnitude of benefit of the intervention or the relative net benefit of alternative courses of action. The panel intends for these moderate-strength recommendations to be used to populate protocols of care and provide a guideline based on the best available evidence. The panel does not intend for weak- or moderate-strength recommendations to generate quality-of-care indicators or accountability measures or affect insurance reimbursement. Variation in care in the areas of weak- or moderate-strength recommendations may be acceptable, particularly in ways that reflect patient values and preferences. Conversely, strong recommendations represent areas in which there is confidence in the evidence supporting net benefit, and the recommendations likely apply to most individuals with SLA. For more information, see exhibit 4.

Existing Systemic Reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines

The expert panel and methodology team identified existing systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines that were relevant to the topics of this guideline, even though they were not necessarily specific to people with SCD. If the methodological quality of these resources was found to be appropriate by the methodology team, they were used. Using this external evidence was considered helpful because well-conducted systematic reviews made the process of identifying relevant studies more feasible. In addition, using existing guidelines developed by professional organizations enabled the panel to develop more comprehensive recommendations that addressed specific aspects of care in individuals with SCD. Usually, this external evidence was derived from studies in non-sickle cell patient cohorts because it was felt that they offered more precise and useful inferences than evidence derived from sickle cell patient studies. For example, comparative evidence in the area of pain management in people with SCD was sparse. In this situation, pain management guidelines from individuals with other pain-related conditions proved to be helpful.

The methodology team used the AMSTAR tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews.30 Recent well-conducted systematic reviews were identified that addressed hydroxyurea therapy in pediatric and adult patients.6 ‘ The expert panel and methodology team appraised these reviews and conducted additional searches to update the existing systematic review through May 2010 to find evidence for the benefits, harms, and barriers of using hydroxyurea. Regarding the management of children with SCD complications, the panel also used recent evidence that had been systematically reviewed.

Existing clinical practice guidelines were considered acceptable if they had prespecified clinical questions, were developed after a comprehensive literature search, had explicit and clear criteria for the inclusion of evidence, and included recommendations that were explicitly linked to the quality of supporting evidence. The expert panel and methodology team used relevant recommendations from the USPSTF, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) adaptation of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) “Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use,”” and the American Pain Society’s “Guideline for the Management of Acute and Chronic Pain in Sickle-Cell Disease,” and “Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain.

Exhibit 2: Evidence Review Process

Exhibit 3: Steps in the GRADE Process

Exhibit 4: Grade Recommendations – A Closer Look