Historical Perspective, Epidemiology, and Methodology

SCD was first reported in the literature in November 1910 by James B. Herrick, who referred to “peculiar elongated and sickle-shaped red blood corpuscles in a case of severe anemia.”’ We have gained substantial knowledge about SCD since that first description. Today there is hope for a cure using hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). However, at present, the procedure is infrequently performed and very expensive. Additional research regarding patient and donor selection and the specific transplantation procedure is required before this potentially curative therapy will become more widely available. Two effective disease-modifying therapies for SC hydroxyurea and chronic transfusion—are potentially widely available but remain underutilized .

The sickle cell mutation results in substitution of the amino acid valine for glutamic acid at the sixth position of the beta globin chain, causing formation of hemoglobin S. More than 2 million U.S. residents are estimated to be either heterozygous or homozygous for the genetic substitution. Most of those affected are of African ancestry or self-identify as Black; a minority are of Hispanic or southern European, Middle Eastern, or Asian Indian descent.” It is estimated that between 70,000 and 100,000 Americans have SCD. Although SCD is associated with major morbidity, currently more than 90 percent of children with SCD in the United States and the United Kingdom survive into adulthood. However, their lifespan remains shortened by two or three decades compared to the general population.

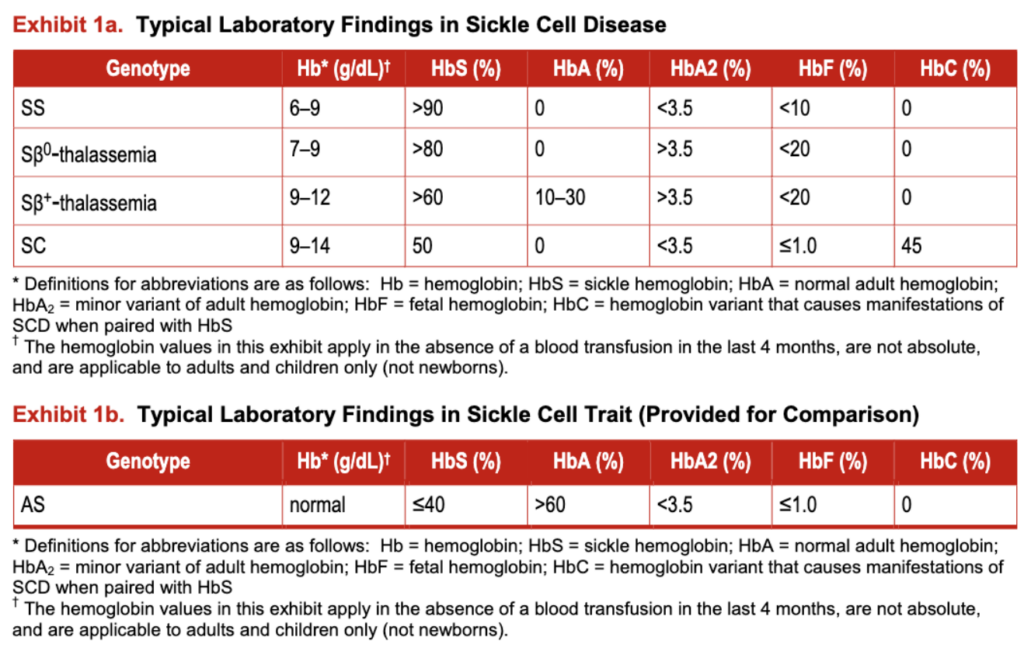

The most prevalent SCD genotypes (exhibit I) include homozygous hemoglobin SS (HbSS) and the compound heterozygous conditions hemoglobin S§0-thalassemia (HbSb0-thalassemia), hemoglobin S§ -thalassemia (HbSb’-thalassemia), and hemoglobin SC disease (HbSC). HbSS and HbS§O-thalassemia are clinically very similar and therefore are commonly referred to as sickle cell anemia (SCA); these genotypes are associated with the most severe clinical manifestations. These guidelines are not applicable to individuals with sickle cell trait (HbAS), the carrier state.

Currently in the United States, there are no comprehensive, systematically reviewed, evidence-based guidelines to assist health care professionals in the management of individuals with SCD. Providing care to these individuals can be challenging. As a result of the condition’s relative rarity, there are few health care professionals who are prepared to deliver continuity care or expert consultation for patients with serious acute or chronic SCD complications. These guidelines are therefore being made available to help provide the latest evidence-based recommendations to manage this condition and to help engage health care professionals in supporting their implementation at the practice level.

Exhibit 1a: Typical Laboratory Findings in Sickle Cell Disease

Exhibit 1b: Typical Laboratory Findings in Sickle Cell Trait (Provided for Comparison)